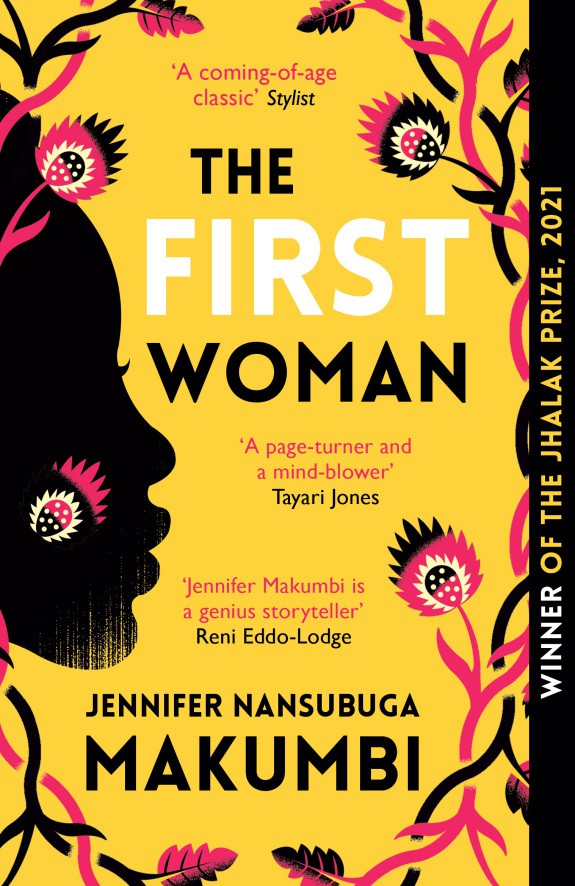

The First Woman by Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi

At the beginning of the book The First Woman seems to be about a favorite grandchild, who does not know her mother, called Kirabo. Kirabo lives with her grandparents and several young cousins and relatives who are simply referred to as ‘the teenagers’. An avid storyteller and fiery spirited child, Kirabo soon finds out that the ‘original state’ of women is living in her. She is unable to discuss this with her grandparents, friends nor the teenagers and so she turns to the village witch. The village witch is called Nsuuta and she shares a particularly complicated history with Kirabo’s grandmother.

Nsuuta and Akilisa, Kirabo’s grandmother, had been best friends when they were young but this relationship was compromised by a pact made as children and a hyper critical society. As the book continues the reader realizes that the story is actually about Akilisa and Nsuuta and how these two old women have lived their life through the decisions they made but also through decisions that where imposed on them merely for being women. Nsuuta especially is an passionate believer of mwenkanonkano and teaches Kirabo to be forgiving of the women around her as often they find themselves in impossible situations. This is perfectly shown in the book in a short discussion between two characters, one woman and one man:

…Ssozi was heard exclaiming, ‘Women, kdto. They are like Zungu chickens in a pen. If you don’t debeak them they turn on each other and peck, kyo-kyo, kyo-kyo, kyo-kyo.’

Nsangi shot up like a teenager…. ‘Mr Sozi,’ she called too politely, ‘I am only asking like a chicken does; why keep the Zungu chickens in confinement? Why not let them out to roam and scratch and peck at insects and worms and see if they come home in the evening and peck each other? Why debeak hens for something you are doing wrong?’

(p.344)

In this manner the book manages to show that often when women mistreat or are evil to one another they are reacting to a hostile environment rather than acting on their own volition. More than this, Makumbi shows too how women continue to fight against their oppression. She shows the bravery of women who dare to speak up and challenge culture and how these women have been around for centuries, so far back in history that their stories are even told as myths. She also shows how mwenkanonkano is rooted in the ways of the Buganda whose women have always advocated for their rightful place in society.

What I love most about this book is that it shows the diversity of women and the different paths they may take to carve out their path in a patriarchal society. Makumbi does not demonize women who wonder away from the traditional path in, for example, not getting married. Makumbi shows that there is an infinite diversity of women and their lives in Uganda in both the past and the present and that this diversity will inevitably continue in the future. This is a book that any advocate for mwenkanonkano would love and one that everyone should read is the chance presents itself, especially all of our brothers.